Developing cost-sharing models for provision of improved water in local communities

The supply and management of water in South Africa is governed by the National Water Act (No. 36 of 1998) and Water Services Act (No. 108 of 1997). The Water Services Act makes provision for the establishment of Water Service Authorities (“WSA”). Section 11 of the Water Services Act states that a WSA has the “duty to all consumers or potential consumers in its area of jurisdiction to progressively ensure efficient, affordable, economical and sustainable access to water services.” A WSA is empowered to appoint a Water Services Provider (“WSP”). The Water Services Act appears to envisage a scenario where the WSA manages the implementation of water provision and the WSP undertakes the actual delivery of the service. Section 20 of the Act allows a WSA to act as a WSP concurrently.

Historically, supply and costing models have focussed on the supply of bulk water (often by a regional water supply service provider) to municipalities, who would then on-sell or provide that water to communities. These systems are often able to rely on economies of scale – the systems are complex and larger municipalities are able to pay for services.

In recent times, there has been added pressure to supply water to smaller municipalities and outlying (often rural) areas. The bulk supply model does not necessarily work for these areas.

Major barriers to providing water in rural areas are the costs of infrastructure investment and the ongoing costs of water provision, as well as a reduced ability to monitor and control the use of water infrastructure by users, due to large distances between the water provider and communities.

Another key consideration is the availability of skills in rural areas to ensure the continuous supply of safe water. Our research has pointed to the following aspects in this regard:

- Municipalities indicated a shortage of water quality analyst skills. Relevant occupations that municipalities have indicated are hard-to-fill in this regard include: Water Production and Supply Manager, Water Quality Analyst & Maintenance Planner.

- The low degree of revenue collection frustrates the provision of regular and necessary maintenance on reticulation systems

The above listed constraints raise challenges in ensuring consistent water supply and safe drinking water.

Contemporary costing models need to account for and serve spatially diverse and divided communities. These models and systems need to be able to monitor and control the supply of water across significant distances to outlying communities.

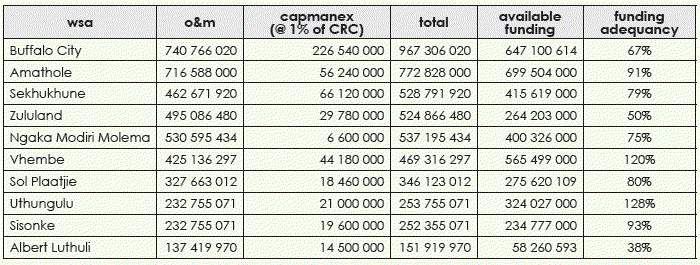

The table below highlights the extent to which 10 municipalities are not able to cover their operating costs.

(Water Research Commission, 2013)

The table above indicates that only 2 out of 10 municipalities (Vhembe and Uthungulu) have adequate funding available to cover their expenses in the provision of water. This indicates that many municipalities are not supplying water on an economically viable and sustainable basis.

To mitigate these barriers, this article suggests a hybrid between a Public-Private Partnership (“PPP”) and a community-based (“CB”) approach. It should be noted that there are examples of successful practices relating to sustainable water provision, both in South Africa and abroad. One municipality consulted mentioned the PPP model adopted in Mbombela as a success story.

Therefore, this article does not attempt to reinvent the proverbial wheel, but rather seeks to adapt existing practices for the South African context.

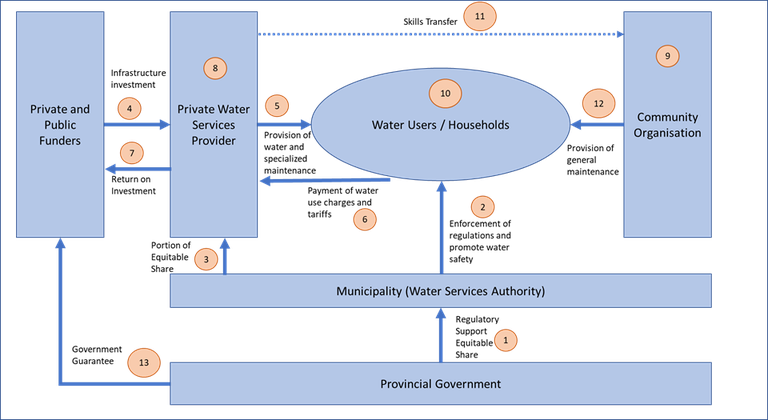

The design of the hybrid PPP-CB model, as depicted below, is intended to promote ownership of the water infrastructure by the community that benefits from the infrastructure.

For this model to be effective, national and provincial government would be required to allocate equitable share and provide regulatory support (1), and local Government will have to enforce regulations (2), promote water safety (2) and provide a portion of the equitable share to the WSP (3). The infrastructure set-up for this model is envisaged to be funded by private and public sectors (4), who would expect a return on investment (7). To attract investors to what may be perceived as a high-risk investment, government should provide a guarantee on investment (13).

Partnering with community organisations (12), the WSP would be responsible for providing both the water and maintenance or repair services (5), to users, who will bear the costs (6). Prepaid and smart meters are recommended to improve revenue collection (10). The private sector would offer specialised skills (8) and capacitate community members through skills-transfer programmes (11). The sense of ownership established by incorporating the community in the provision of services may reduce vandalism and abuse of infrastructure (9).

This article highlighted the need for a new costing model for water provision in some contexts, most notably the rural context. It was established that the supply of water in rural areas is hampered by:

- The extent to which costs are recovered through paying-users

- Vandalism, which appears to be more prevalent in rural areas

- The fact that more piping is often required in rural areas

- Ease of access for maintenance teams across rural areas

- The feasibility and difficulty of recycling water

The article puts forward a Community-Based, Public-Private Partnership model to help address these water supply challenges. This should lead to a situation where communities are more self-sufficient in maintaining their water infrastructure.

Community ownership and involvement is important as, in the long term, extensive private sector involvement may not be to the benefit of communities since water is a social good, which may not be completely in line with the private sector’s profit-making incentive.

Key training interventions required to realise this model include:

- Project management

- Quality control

- Budget management

- Negotiation skills

- Management related skills

The CB-PPP model proposed has the potential to reduce expenditure by government, as well as increase water provision to currently underserved and hard to reach rural communities.

This article is part of a series reporting on research commissioned by the Local Government Sector Education & Training Authority (LGSETA) (Contact: matodzir@lgseta.org.za)

The publication of the Bulletin is made possible with the support provided by the Hanns Seidel Foundation and the Bavarian State Chancellery.